The Macintosh Revolution: 1983-85

4-frogdesign || 5-Corporate focus || Conclusion || Bibliography & links

![]()

![]()

While IBM represented the PC as friendly, contrary to its appearance and conservative functions, Apple worked on innovative technology that would dramatically improve the ease of using a computer. The graphical user interface generated for Apple's next major computer was inspired by what a small group of visitors from Apple saw at Xerox's Palo Alto Research Center. Allowed brief access to PARC in exchange for a discounted price on Apple stocks in December 1979, Steve Jobs, a software programmer named Bill Atkinson, and several Apple engineers felt that they had seen the future of computing. They had. PARC had developed, and Xerox had failed to market, a computer that used a mouse to negotiate between "windows" using the metaphor of a desktop that is now implemented on virtually all personal computers. Rather than amber or green characters appearing on a black background, the Alto's display had the black-on-white appearance of paper. This was generated by "bit-mapping," a method of turning on or off each pixel independently that allows complete control over the appearance of letters and images. This exact display, together with the use of icons and windows in the desktop metaphor, allowed the Alto's interface to be explored intuitively as a physical space (Levy, 65-79).

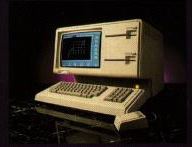

After hiring several engineers

from Xerox PARC, Apple recreated and improved the bitmapped

display and desktop interface. This techno logy would first appear in

the Lisa, a computer intended for businesses. Priced at $9

995 when introduced in January of 1983, however, the Lisa

would be a commercial failure

(Kunkel, 20).

logy would first appear in

the Lisa, a computer intended for businesses. Priced at $9

995 when introduced in January of 1983, however, the Lisa

would be a commercial failure

(Kunkel, 20).

Apple Lisa (1983)

Steve Jobs had attempted to administer control over the Lisa's appearance and features, but he annoyed his engineers to the degree that he was eventually alienated from the project (Kunkel, 19). Feeling slighted and disturbed by the increasingly disunified, corporate environment of Lisa's development, Jobs was excited to discover a quiet "skunkworks" - an unofficial project at Apple - that reflected the fervent hobbyist atmosphere that had surrounded Steve Wozniak's Apple II. Jobs insinuated himself into the small group working on this personal vision of computing in late 1980, and gradually he took it over (Levy, 117).

The original conception of the Macintosh was made by a former computer science professor who became a designer at Apple, Jef Raskin. Raskin wanted to create a computer that would not merely appear, but actually work as an appliance; it would not require adjustments or arcane knowledge. It was to be a computer for people who were not fascinated in learning how it worked. Raskin's idea was to have a machine even more self-contained than the Macintosh eventually was, with everything - keyboard, screen, even software on pre-programmed chips - in one case (Rose, 50-1).

Two prototypes for Raskin's Macintosh were developed in 1980 by a single, self-taught engineer who worked in Apple's repair shop, Burrell Smith. When Steve Jobs saw Smith's work, he believed that, if continued as the work of a small group of closely connected designers and engineers sharing a personal vision, the Macintosh could bring the dramatic change in how people interact with computers that he had imagined when he saw Xerox PARC's Alto. Jobs raved that the Macintosh would be revolutionary - "insanely great" - and the group that became dedicated to the project came to believe him. With Jobs' influence, the Macintosh began to look increasingly like a less expensive version of the Lisa, meant for a general public rather than businesses. Raskin, who wanted to adhere pedantically to his own design concept despite the outside innovations suggested by the Alto, eventually abandoned the project (Levy, 114-23).

Jobs and the Macintosh team worked

very closely together in a spirit of revolution; they were

going to democratize computing. Jobs had always considered

the development of computers to have a large social

dimension, but the Macintosh project seems to have been even

more important socially than technically to him. He

recruited John Sculley, then CEO of Pepsi, to head Apple in

late 1982 by asking, "Do you want to spend the rest of your

life selling sugared water or do you want a chance to change

the world?"

(Sculley, 90). O ften said to have a "Reality

Distortion Field" of charisma, Jobs seemed to persuade

others to share his vision, and the Macintosh team has been

repeatedly described as "cultish and fanatic"

(Levy, 140-2), working

with "religious fervor . . . driven by the unanimous belief

that they had an opportunity to change the ways people work

and think"

(Fluegelman, 126).

Jobs encouraged the Mac team to consider themselves artists

and renegades. Two of Jobs' epigrams offered to the team

were to become clichés at Apple: "Real artists ship"

encouraged results from design strategy; "It's better to be

a pirate than to join the Navy" established the designers as

radicals. A skull and cross-bones flag flew over their

building at Apple Computer despite the corporate structure

that could generate the failed and misdirected Lisa. The

Macintosh was to bring the same ease of use to "the rest of

us" in a friendlier form

(Rose, 55-8).

ften said to have a "Reality

Distortion Field" of charisma, Jobs seemed to persuade

others to share his vision, and the Macintosh team has been

repeatedly described as "cultish and fanatic"

(Levy, 140-2), working

with "religious fervor . . . driven by the unanimous belief

that they had an opportunity to change the ways people work

and think"

(Fluegelman, 126).

Jobs encouraged the Mac team to consider themselves artists

and renegades. Two of Jobs' epigrams offered to the team

were to become clichés at Apple: "Real artists ship"

encouraged results from design strategy; "It's better to be

a pirate than to join the Navy" established the designers as

radicals. A skull and cross-bones flag flew over their

building at Apple Computer despite the corporate structure

that could generate the failed and misdirected Lisa. The

Macintosh was to bring the same ease of use to "the rest of

us" in a friendlier form

(Rose, 55-8).

Macintosh (1984)

Home || Introduction || Historiography || 1-Cottage industry || 2-Emerging standards || 3-Macintosh

4-frogdesign || 5-Corporate focus || Conclusion || Bibliography & links

.jpg)