History of computer design: Apple III

4-frogdesign || 5-Corporate focus || Conclusion || Bibliography & links

![]()

![]()

Apple had reached outside of the small

number of hobbyists on which other companies focused to

attract the growing home and school markets. At the same

time, the Apple II remained the most popular hobby computer

because of its open architecture - "an entire subindustry"

emerged to add functionality to the Apple II via its many

expansion ports

(Moore, 68). To add to

its great success, Apple began designing a computer

specifically for businesses in 1978. Unlike Wozniak's Apple

II, the Apple III was designed by committee, features

continually being added by the many engineers and marketers

involved. Apparently no one doubted the machines' success.

One engineer, Richard Jordan, recalled the atmosphere around

the Apple III design, saying, "As Apple's stock price took

off, we all felt like geniuses, even though most of us had

nothing to do with the Apple II . . . Pretty soon, we

figured that it was impossible for us to fail, no matter

what we did" (Kunkel,

16). When the Apple III belatedly appeared in September

1980, it failed, not just commercially, but literally. With

too many components causing electrical shorts, it reportedly

had a nearly 100% failure rate

(Smarte, 381).

Apple had reached outside of the small

number of hobbyists on which other companies focused to

attract the growing home and school markets. At the same

time, the Apple II remained the most popular hobby computer

because of its open architecture - "an entire subindustry"

emerged to add functionality to the Apple II via its many

expansion ports

(Moore, 68). To add to

its great success, Apple began designing a computer

specifically for businesses in 1978. Unlike Wozniak's Apple

II, the Apple III was designed by committee, features

continually being added by the many engineers and marketers

involved. Apparently no one doubted the machines' success.

One engineer, Richard Jordan, recalled the atmosphere around

the Apple III design, saying, "As Apple's stock price took

off, we all felt like geniuses, even though most of us had

nothing to do with the Apple II . . . Pretty soon, we

figured that it was impossible for us to fail, no matter

what we did" (Kunkel,

16). When the Apple III belatedly appeared in September

1980, it failed, not just commercially, but literally. With

too many components causing electrical shorts, it reportedly

had a nearly 100% failure rate

(Smarte, 381).

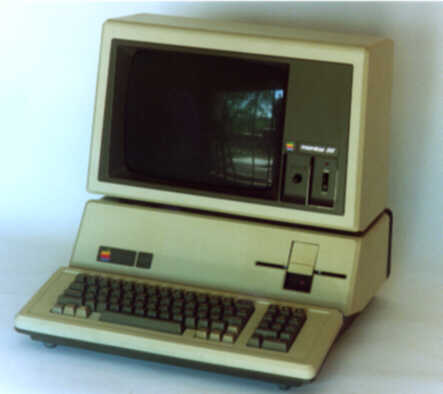

The failure of the Apple III began with the design of its case. Jerry Manock and a contracted industrial designer, Dean Hovey, completed the basic design for the case before its circuitry was complete. Late changes made by another Apple designer, Bill Dresselhaus, would be superficial, so that the design of the electronics was shaped by an existing form. This illustrates the then unique importance placed by Apple on the physical appearance of its machines; Apple valued case design enough to contradict the practice of the hobby market from which it had emerged by subordinating the elegance of electronics to that of its enclosure. FCC guidelines for electromagnetic shielding not yet available, Manock and Hovey designed an aluminum chassis for the interior of the case, using space requirements initially given by engineers. As features grew, this chassis, already cast, became increasingly crowded. Steve Jobs insisted, as he had done with the Apple II, that the Apple III be an appliance. To Jobs, this meant that there would be no fan to dissipate the heat generated from its densely packed components; he considered the noise of a fan to be industrial and "inelegant" (Kunkel, 16). Though the Apple III design was improved in 1981 and again in 1983, when it was renamed the Apple III+, it sold very poorly and was finally discontinued in 1985.

Though it ironically led to its own failure through its perceived importance, the Apple III case successfully expresses the adaptation of the Apple II style to a business environment. The keyboard appears as a separate unit in front of the computer itself. This separation would quickly emerge as a standard characteristic for computers designed for business. Without the integrated keyboard, the Apple III seems more boxy than the Apple II, but it is also not as long. Its front bezel is angled up towards the user, elevated about the keyboard in a gesture that facilitates and encourages interaction with its integrated floppy drive. The corners on both the computer and the keyboard share the 45-degree chamfers that Manock had used for the Apple II, and the same placement of the name badge and identical beige plastic help reinforce the impression that the Apple III is a less frivolous but close relative to its predecessor.

To Emerging Standards

(1980-82) ![]()

Home || Introduction || Historiography || 1-Cottage industry || 2-Emerging standards || 3-Macintosh

4-frogdesign || 5-Corporate focus || Conclusion || Bibliography & links

.jpg)